Pastoral

Ninguno, porque a los que no mató

huyeron.

Un pastor le pegó un tiro a un árbol

lleno de pájaros y mató a unos cuantos.

¿Cuántos quedaron?

No son flores lo que faltan,

ni abundancia de árboles,

ni fuente para sazonar

árboles y flores.

Violently funny.

"La luz es el primer animal visible de lo invisible" --Lezama

Saturday, November 12, 2011

Joan Ramón Resina on Maragall

Two excellent characterizations of Maragall's work.

The poet perceives the majesty of the sacred in the “living word,” which is language so close to nature that it is just at the point of blending into the landscape or perhaps emerges from it (199).

“A subtle movement of the air,” says Maragall, “places before you the immense variety of the world and arouses in you a strong sense of the infinite unknown" (200).

Thursday, November 3, 2011

A literary angle

I really enjoyed reading Annabel Martín's "Critical Basque Studies" about a month ago and its equally interesting now. In particular, I like her suggestion, following Adrienne Rich, that literature slows down the intelligible world and brings us metaphorically to the unintelligible or invisible.

In the case of literature, this would entail a writer's unique struggle with language to name the unknown, with the writer's attempt to give form through metaphor to the unintelligible, with being truthful to the complexity of reality, with learning how to suspend a "netted bridge over a gorge." (177)

The literary attitude calms down its objects of inquiry, categories that no longer merely consist of books but a plethora of cultural objects. Martín is shy to utterly shun literature in the face of cooler, shiner texts. Yet she does not discount the importance of other mediums (nor do I). Instead, she looks back to the literary as a way to again urge for engaged questioning in the public sphere. This has everything to do with my work on causality between Merleau-Ponty and Lezama Lima, which attempts to evaluate their forms of phenomenology in relationship to object-oriented thinking (including poetics and ontology). The category of the unintelligible might be extended to consider the invisible, the unthinkable and the horrific, to name a few. Literature gives a space to engage the gaps and holes in human thinking, not necessarily to provide neat answers but to unravel their yarns in messy situations.

In the case of literature, this would entail a writer's unique struggle with language to name the unknown, with the writer's attempt to give form through metaphor to the unintelligible, with being truthful to the complexity of reality, with learning how to suspend a "netted bridge over a gorge." (177)

The literary attitude calms down its objects of inquiry, categories that no longer merely consist of books but a plethora of cultural objects. Martín is shy to utterly shun literature in the face of cooler, shiner texts. Yet she does not discount the importance of other mediums (nor do I). Instead, she looks back to the literary as a way to again urge for engaged questioning in the public sphere. This has everything to do with my work on causality between Merleau-Ponty and Lezama Lima, which attempts to evaluate their forms of phenomenology in relationship to object-oriented thinking (including poetics and ontology). The category of the unintelligible might be extended to consider the invisible, the unthinkable and the horrific, to name a few. Literature gives a space to engage the gaps and holes in human thinking, not necessarily to provide neat answers but to unravel their yarns in messy situations.

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

"Hay que humanizarse o perecer"

Humanize or perish, Goytisolo's youthful response to Ortega y Gasset's deshumanización del arte. Yet this return to realism did not entail a collapse back into the gigantic tomes of Galdós or Balzac, but a new attention to what could be experienced through sensory perception. I find this interesting because of the major chasm constructed between the author's realist work and his experimental work, beginning with the Álvaro Mendiola trilogy. I am not, of course, prone to draw too many comparison between various markers on Goytisolo's trajectory, but one must always wonder how it might even be considered a trajectory -- if that is the proper word.

"The landscape set burning"

Atxaga's Obabakoak is obsessed with its own backdrop. I found this fragment lurking in my notes this evening:

Naturally my friend didn't know who I meant and so I settled down to the eleventh memory of the night--too many perhaps for one journey, too many, even, for one book. But that night my memory was like dry tender which the heat generated by the landscape set burning. (203)

This passage was epiphanic for me this summer. Tonight I remember why.

Naturally my friend didn't know who I meant and so I settled down to the eleventh memory of the night--too many perhaps for one journey, too many, even, for one book. But that night my memory was like dry tender which the heat generated by the landscape set burning. (203)

This passage was epiphanic for me this summer. Tonight I remember why.

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Beyond Romantic Nature: the Baroque

I am really enjoying The Poet and the Natural World in the Age of Góngora because Michael Woods is shifting away from a purely (or naively) Romantic conception of Nature. He follows Emilio Orozco's Paisaje y sentimiento de la naturaleza en la poesía española, to argue that a form of the pictorial landscapes (e.g. Nature qua esthetic category) begins in the 16th century.

The difference between a Romantic Nature and Baroque Nature is precisely its sentiments towards the nonhuman world. In Góngora, for instance, these sentiments are infamously "nebulous". To quote Dámaso Alonso:

Everwhere...there flows an awed spirit of exaltation in natural forces: beneath the most precise lines, beneath the most splendid words, there lies the vital flame of creative and regenerative nature, like a passionate ebullience" (71).

As Woods points out, there are several aspects of this marvelous sentence that should be read with care. For me, what it might mean to suggest a "vital flame" of regeneration. On whose part? Woods takes us in an interesting direction on this point, to suggest that it is the sincerity of the poem that might lead us the particular constructedness of a natural poetics.

The difference between a Romantic Nature and Baroque Nature is precisely its sentiments towards the nonhuman world. In Góngora, for instance, these sentiments are infamously "nebulous". To quote Dámaso Alonso:

Everwhere...there flows an awed spirit of exaltation in natural forces: beneath the most precise lines, beneath the most splendid words, there lies the vital flame of creative and regenerative nature, like a passionate ebullience" (71).

As Woods points out, there are several aspects of this marvelous sentence that should be read with care. For me, what it might mean to suggest a "vital flame" of regeneration. On whose part? Woods takes us in an interesting direction on this point, to suggest that it is the sincerity of the poem that might lead us the particular constructedness of a natural poetics.

Monday, October 24, 2011

Pirenenqes // Pirenaicas

After a late evening filled with baroque poetry and a morning of modernist poetry, these lines from Maragall stand out -- as far as the etching of landscape is concerned.

I em vaig tobant tan bé an allà entremig

i em ba invadint com una immensa pau,

i vaig sent un troç mès del prat suau

ben verd, ben verd sota d'un cel ben blau.

Y cada vez más a gusto en este entorno

me ba invadiendo una inmensa paz,

me voy sintiendo parte de este prado

tan verde y suave bajo el cielo azul. (55)

The Spanish translation from the Catalan slightly displaces suau and misses the repetition at work in the last lines, which emphasizes a sort of continuity between the color (verd), its adverb (ben) and a texture (suau). To speak a bit more on the translation, there is also a cool discrepancy between entorno and entremig. The former implies the surroundings of a single point, where the latter actually gestures at a space between two different points (spatially or temporally). This last point is crucial in the dissection of landscape poetics because one text emphasizes a singular viewpoint, whereas the other (the Catalan original), thinks between at least two points.

This last point plays out significantly in the poem's situation because in the previous sections, Maragall moves from an isolated mountain landscape, which is etched out through a series of negations ("les flors són esblaimades / les flors són d'un blau clar, / blavoses o morades;") to a more humanized environment. This is carried through the mediating metaphor of the child (la niña mimada / la nina aviciada), a figure he likens to the mountain mist. This movement (in the immobile mountain range) transports us to a coded environment that seems like a town. The intricacies of the poem play out between these two places.

I em vaig tobant tan bé an allà entremig

i em ba invadint com una immensa pau,

i vaig sent un troç mès del prat suau

ben verd, ben verd sota d'un cel ben blau.

Y cada vez más a gusto en este entorno

me ba invadiendo una inmensa paz,

me voy sintiendo parte de este prado

tan verde y suave bajo el cielo azul. (55)

The Spanish translation from the Catalan slightly displaces suau and misses the repetition at work in the last lines, which emphasizes a sort of continuity between the color (verd), its adverb (ben) and a texture (suau). To speak a bit more on the translation, there is also a cool discrepancy between entorno and entremig. The former implies the surroundings of a single point, where the latter actually gestures at a space between two different points (spatially or temporally). This last point is crucial in the dissection of landscape poetics because one text emphasizes a singular viewpoint, whereas the other (the Catalan original), thinks between at least two points.

This last point plays out significantly in the poem's situation because in the previous sections, Maragall moves from an isolated mountain landscape, which is etched out through a series of negations ("les flors són esblaimades / les flors són d'un blau clar, / blavoses o morades;") to a more humanized environment. This is carried through the mediating metaphor of the child (la niña mimada / la nina aviciada), a figure he likens to the mountain mist. This movement (in the immobile mountain range) transports us to a coded environment that seems like a town. The intricacies of the poem play out between these two places.

Sunday, October 23, 2011

Quevedo aiding Alonso

Elena González Quintas provides a lot of helpful analysis of metaphoric values (de la naturaleza y la mujer) in Quevedo. She makes an excellent point in her concluding paragraph on natural metaphors: Quevedo's revamp of baroque metaphors accomplishes two things -- 1) Distancing the imaginary term from the real (signifier from the signified) 2) to magnify the qualities of the referent (164). This seems to be Alonso's suggestion about real objects returning "with a vengeance". It also seems to be Tim Morton's suggestion on what Derrida's "sin of omission" might look like. Agreed. Agreed.

Realzar: A fascinating entry in DRAE

This verb fascinates me. Predominantly because of the fourth definition and the work I have done on light and causality.

Real Academia Española © Todos los derechos reservados

1. tr. Levantar o elevar algo más de lo que estaba. U. t. c. prnl.

Eugeni d'Ors avoiding the flash points of contrapunteo

There should be little mistake about d'Ors noucentisme project. He wants to make life like his conception of the work of art: ordered, harmonious, and serene in all of its "realización plástico-literaria", as he puts it in the prologue to La ben plantada. This literary-plasticity, speaking of a text that has been chiseled away into visual symmetry, represents what Cataluña looked like (read should look like) in the eyes of D'ors. It predicates from an insulated landart, built to shut out too much Nature (we have the Romantics to thank for that move, according to D'ors), and too much urbanism. These esthetic pieces are whittled down into nubs so that they might fit together. Any conceivable excess is boiled off (or carved out, to continue the sculpture analogy).

Yet I have just stumbled across an interesting text of his, Poussin y el Greco, which provides a contrast between Poussin, "the artist of the philosopher" from el Greco, "the artist of the spirits (which d'Ors connects to poetry). What interests me is the countervalence he establishes between the two painters.

La tierra nos atrae. Parece que de esta atracción la vida puede emanciparse de dos maneras: volando o manteniéndose en pie. Volar es más poético; pero mantenerse en pie es más noble.

El Greco: pintor de las formas que vuelan. Poussin: pintor de las formas que se mantienen en pie. (16)

The distinction here develops from different types of movements. Demonic forms in a flux of flight patterns and others that are allowed to remain "backdrops". There are a variety of reading strategies that should highlight the flash point between these forms as focus points and forms as backdrops. The result would produce more instability than d'Ors would care to admit.

Yet I have just stumbled across an interesting text of his, Poussin y el Greco, which provides a contrast between Poussin, "the artist of the philosopher" from el Greco, "the artist of the spirits (which d'Ors connects to poetry). What interests me is the countervalence he establishes between the two painters.

La tierra nos atrae. Parece que de esta atracción la vida puede emanciparse de dos maneras: volando o manteniéndose en pie. Volar es más poético; pero mantenerse en pie es más noble.

El Greco: pintor de las formas que vuelan. Poussin: pintor de las formas que se mantienen en pie. (16)

The distinction here develops from different types of movements. Demonic forms in a flux of flight patterns and others that are allowed to remain "backdrops". There are a variety of reading strategies that should highlight the flash point between these forms as focus points and forms as backdrops. The result would produce more instability than d'Ors would care to admit.

D. Alonso on Flowers in Spanish Poetry

In his essay "Flores en la poesía de España" Dámaso Alonso speculates on the nonexistence of a Spanish Generation of the flowers. For Alsono, this is a symptom of Spanish Romanticism's deficiency. Its height never reached the legacy of Wordsworth, for instance.

The Generation of 98 was the Generation of landscape but failed to focus on the flora inhabiting (or not) those endless terrains. It is only with Juan Ramón Jiménez that the reader again encounters a focus on flower tone poems.

Alonso then returns to a brief reflection on the Baroque and barroquismo (the recycling of baroque style) and gives a rather interesting definition of the baroque relationship to nonhumans.

Nóstese, porque es importante, que el procedimiento de muchos de estos retratos hay humor, es decir, que son un tipo de «caricatura». Así, el barroquismo llega a la realidad, por la elusión de la realidad, por la hiberbólica imagen. En arte lo real tiene siempre su venganza. (284)

What I like about this description is its avoidance of stronger claims made about baroque esthetics concerning the distance between things and language (Foucault). Instead, a similar argument is released: language approaches reality through "elusión" and the hyperbolic image but "lo real" is not simply a phantom, but rather an etched out shadow image, lying in wait with vengeance. So much for the simple loveliness of flowers...

The Generation of 98 was the Generation of landscape but failed to focus on the flora inhabiting (or not) those endless terrains. It is only with Juan Ramón Jiménez that the reader again encounters a focus on flower tone poems.

Alonso then returns to a brief reflection on the Baroque and barroquismo (the recycling of baroque style) and gives a rather interesting definition of the baroque relationship to nonhumans.

Nóstese, porque es importante, que el procedimiento de muchos de estos retratos hay humor, es decir, que son un tipo de «caricatura». Así, el barroquismo llega a la realidad, por la elusión de la realidad, por la hiberbólica imagen. En arte lo real tiene siempre su venganza. (284)

What I like about this description is its avoidance of stronger claims made about baroque esthetics concerning the distance between things and language (Foucault). Instead, a similar argument is released: language approaches reality through "elusión" and the hyperbolic image but "lo real" is not simply a phantom, but rather an etched out shadow image, lying in wait with vengeance. So much for the simple loveliness of flowers...

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Unamuno

Teaching Unamuno's San Manuel always draws me into different speculations. This was the first Spanish novel I read years ago, and in many ways, a text that haunts me. This admission itself has become somewhat of a disciplinary oddity. Most Hispanists want to either avoid, dismiss or comfortably forget about Unamuno and his "Generation's" España oscura. (This tendency is curious in light of what one professor recently told me: a specialist in Latin American literature said it was a tragedy that Unamuno has become so overdetermined in the peninsular tradition. Geographical issues aside, I wonder what would happen if Latin Americanists attempted to claim him?) For practical reasons, I do not have this luxury of forgetting. One of my exam questions departs from the obsessive trope of landscape in the Generation of 1898. I have looking into their own roots in the Insitución Libre de Enseñanza, krausismo and the political atmosphere of the 19th century.

As a sort of pretext to switch from the short story to the novel, we discussed several descriptions of the novel from Kundera, Vargas Llosa, J. Goytisolo and Borges. So throughout this reading, I returned again to the peculiar framing at work in San Manuel. Ángela begins to narrate her memories of San Manuel and slowly disappears into the dialogues and anecdotes of her text. Her voice fuses into a multiplicity of narrators and audiences. Put differently, other voices and objects seep into her text, calling attention to their own presences and projects. Among these latter entities, the final authorial voice is not Ángela's but Unamuno's. He shifts her "confesión íntima" into a sort of confusion. She concludes:

Y al escribir ahora, aquí... cuando empiezan a blanquear con mi cabeza is recuerdos, está nevando, nevando sobre el lago, nevando sobre la montaña.... Y no sé lo que es verdad y lo que es mentira, ni lo que vi y lo que soñe. (129)

This passage again calls attention to landscape. Not so much as a discrete collection of external entities, but rather as a dimly lit interior terrain. Yet this interiority is not completely sealed away but forced to touch a community of voices, those of her narrative. The same might be said of Unamuno's rurality. Despite Unamuno's presentation of a rural ambience untouched by modernization or History (en mayúscula). It cannot remain pure and outside of History. Instead, Ángela herself causes them to touch and repel from one another (her education in Renada and, of course, her brother's rhetoric).

The confusion of "la confesión íntima" results in a transference from a letter to a novel, a genre that Unamuno determines is "el más íntimo". This last point is counterintuitive. How is a novel more intimate than a poem? The former is often perceived as a packed space, full of voices and story lines while that latter is often a concentrated mediation of the lyric function. In light of my comments above, it seems that Unamuno's suggestion is precisely about the relations between the various metaphors and narrative layers. His "novela de tesis" is not some ironic posturing, but a sincere (albeit feigned on certain levels) between different modes of thinking and being.

As a sort of pretext to switch from the short story to the novel, we discussed several descriptions of the novel from Kundera, Vargas Llosa, J. Goytisolo and Borges. So throughout this reading, I returned again to the peculiar framing at work in San Manuel. Ángela begins to narrate her memories of San Manuel and slowly disappears into the dialogues and anecdotes of her text. Her voice fuses into a multiplicity of narrators and audiences. Put differently, other voices and objects seep into her text, calling attention to their own presences and projects. Among these latter entities, the final authorial voice is not Ángela's but Unamuno's. He shifts her "confesión íntima" into a sort of confusion. She concludes:

Y al escribir ahora, aquí... cuando empiezan a blanquear con mi cabeza is recuerdos, está nevando, nevando sobre el lago, nevando sobre la montaña.... Y no sé lo que es verdad y lo que es mentira, ni lo que vi y lo que soñe. (129)

This passage again calls attention to landscape. Not so much as a discrete collection of external entities, but rather as a dimly lit interior terrain. Yet this interiority is not completely sealed away but forced to touch a community of voices, those of her narrative. The same might be said of Unamuno's rurality. Despite Unamuno's presentation of a rural ambience untouched by modernization or History (en mayúscula). It cannot remain pure and outside of History. Instead, Ángela herself causes them to touch and repel from one another (her education in Renada and, of course, her brother's rhetoric).

The confusion of "la confesión íntima" results in a transference from a letter to a novel, a genre that Unamuno determines is "el más íntimo". This last point is counterintuitive. How is a novel more intimate than a poem? The former is often perceived as a packed space, full of voices and story lines while that latter is often a concentrated mediation of the lyric function. In light of my comments above, it seems that Unamuno's suggestion is precisely about the relations between the various metaphors and narrative layers. His "novela de tesis" is not some ironic posturing, but a sincere (albeit feigned on certain levels) between different modes of thinking and being.

Saturday, October 8, 2011

More on baroque natures

Fernando R. de la Flor’s “On the Notion of a Melancholic Baroque” provides multiple points of convergence between Benjamin’s thesis on German Tragic Drama and the new historiography of the Spanish Baroque, as evidenced in J. Antonio Maravall. Each work, at once large in scope, but in tune to digging into the human trash heaps of empire, asserts that even if we cleanse our hands of the Baroque, it perpetually returns through a plurality of “ontological crises”.

This final term deserves clarification. It is not so much the disappearance of things that shifts in the Baroque, but rather the qualities commonly associated to them. After an epigone of human reason’s domination of the world, in which science and mathematical formulae not only represent but also encapsulate the world, quotidian objects become weird in their own right. In the 17th century, this created a rift between world and the prison cell of human thinking.

Nature, for instance, was seen as a kind of corollary to the internal mechanisms of human politics. Alongside “forgotten empires” nature provides some sort of foundational harmony for human actors. It was a backdrop for predication. Yet, as R. de la Flor notes, the baroque turns nature into a play of shadow puppets:

Here, one’s attention is directed toward the search for a superior evidence of the mutability of things in nature which is the true ideal “theater” where great changes are worked through, and where nothing ever remains as it is for a long time. In the words of a modern poet nature is the “temple of caducity”. (15)

If nature’s world is kept as some sort of corollary for human behavior or psychology, here we find the instability of natural entities demonstrating the rift between human expectation of how a world should function and its actual ontological status.

Yet a rift does not simply imply complete isolation between the human mind and world but simply a complication in interactions. For instance, the power of nature’s shadow puppets no longer relies on the hands manipulating shards of light but rather dim personae it creates on distant walls. That is to say, imaginary crises become as real as real ones. R. de la Flor suggests as much in his discussion of the imago, which, in my view, projects esthetic objects onto an ontological plane alongside real ones.

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

Idearium español, el molinero

This post continues my bewilderment surrounding the dismissal of ideas and thinkers. This time its tied to el molinero, Ganivet. According to his epilogue his work might have neither head nor feet but walks around on stilts. Its object of study, processing forms of regeneracionismo common to the Generation of 1898, is at once removed (it was written abroad) but also re-connects to the earth through a peculiar humor. Speaking of skies and grounds: "Si no me estrello, voy a llegar hasta las nubes".

This comparison truly become interesting when Ganivet strikes a note with Zubiri on the mysterious inner-workings of objects:

"Cuando yo, siendo estudiante, leí las obras de Séneca, me quedé aturdido y asombrado, como quien, perdida la vista o el oído los recobraba repentina e inesperadamente y viera los objetos, que con sus colores y sonidos ideales se agitaban antes confusos en su interior, salir ahora en tropel y tomar consistencia de objetos reales y tangibles."

This passage describes a tactile contact as an unexpected agitation. A moment when "the interior" reveals "salir en tropel", an unexpected multitude of things, people and ideas. The book itself, the Idearium, is that grinds through these ideas like a mill. It processes instead of proposes.

This comparison truly become interesting when Ganivet strikes a note with Zubiri on the mysterious inner-workings of objects:

"Cuando yo, siendo estudiante, leí las obras de Séneca, me quedé aturdido y asombrado, como quien, perdida la vista o el oído los recobraba repentina e inesperadamente y viera los objetos, que con sus colores y sonidos ideales se agitaban antes confusos en su interior, salir ahora en tropel y tomar consistencia de objetos reales y tangibles."

This passage describes a tactile contact as an unexpected agitation. A moment when "the interior" reveals "salir en tropel", an unexpected multitude of things, people and ideas. The book itself, the Idearium, is that grinds through these ideas like a mill. It processes instead of proposes.

Thursday, September 29, 2011

Maravall on Unamuno

Due to the fact that my reading of Maravall is limited to his work on the Baroque (which I enjoy), I am surprised about the case he makes for Unamuno in his essay "De la intrahistoria a la historia". Of course, the essay takes place in a lengthy volume called Homenaje a Miguel de Unamuno. What surprises me is his upbeat tone. In La cultura del Barroco Maravall is famous for labeling the an entire nexus of culture as a form of state propaganda, a position that (some what) negates some contemporary positions.

In the field of peninsular literature (or what some of us prefer to call Iberian literary studies), the Generation of 98 is often viewed as an oversaturated object of inquiry. On this view, not only has each word of these authors been scrutinized in relation to ever other, but los noventayochistas tend to favor a vision of Spain as Castile (a blanket criticism that overlooks outliers -- like Valle-Inclán). Castile is the microcosm for Spain. All other regions are absorbed into the history and vision of an aged empire. Maravall says something different about Unamuno:

El «hombre sustancial» de que nos habla en «Visiones y comentarios», ese hombre que es alma y carne, que es espíritu y tierra-- esa tierra que es paisaje, creación humana recibida de sus antepasados-- nos lo presenta con frecuencia Unamuno como el individuo arraigado en la soledad campesina. Frente a él, «el hombre de la calle o el de la ciudad, el ciudadano, propiamente el elector, el de partido, es el político, de polis, ciudad; pero el otro, el interior, el de a sus solas, es el individuo del mundo--cosmos--, es el cósmico. (181)

Maravall's discussion begs a few important questions in today's attention or dismissal to Unamuno. They concern me because one aspect of my prelim is a sort of genealogy of literary landscapes in 20th century Spanish literature. I am working to re-invigorate thinking about Unamuno through his contact with a variety of Iberia's nationalisms and the multivalent concept of landscape. Unamuno was Basque. And his correspondence with Maragall is also fascinating. These connections push us to investigate the claim to some sort of cosmos in Unamuno. Indeed, as I have alluded to here, I think U's En torno al casticismo is saturated in dark dormant voices -- not only of humans but of nonhumans, geography and submerged caverns.

In the field of peninsular literature (or what some of us prefer to call Iberian literary studies), the Generation of 98 is often viewed as an oversaturated object of inquiry. On this view, not only has each word of these authors been scrutinized in relation to ever other, but los noventayochistas tend to favor a vision of Spain as Castile (a blanket criticism that overlooks outliers -- like Valle-Inclán). Castile is the microcosm for Spain. All other regions are absorbed into the history and vision of an aged empire. Maravall says something different about Unamuno:

El «hombre sustancial» de que nos habla en «Visiones y comentarios», ese hombre que es alma y carne, que es espíritu y tierra-- esa tierra que es paisaje, creación humana recibida de sus antepasados-- nos lo presenta con frecuencia Unamuno como el individuo arraigado en la soledad campesina. Frente a él, «el hombre de la calle o el de la ciudad, el ciudadano, propiamente el elector, el de partido, es el político, de polis, ciudad; pero el otro, el interior, el de a sus solas, es el individuo del mundo--cosmos--, es el cósmico. (181)

Maravall's discussion begs a few important questions in today's attention or dismissal to Unamuno. They concern me because one aspect of my prelim is a sort of genealogy of literary landscapes in 20th century Spanish literature. I am working to re-invigorate thinking about Unamuno through his contact with a variety of Iberia's nationalisms and the multivalent concept of landscape. Unamuno was Basque. And his correspondence with Maragall is also fascinating. These connections push us to investigate the claim to some sort of cosmos in Unamuno. Indeed, as I have alluded to here, I think U's En torno al casticismo is saturated in dark dormant voices -- not only of humans but of nonhumans, geography and submerged caverns.

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Borges

Just after finishing the previous post, I am reviewing some information on JLB. I am teaching "El etnógrafo" y "Los dos reyes y los dos laberintos"and came across this idea, which has a lot to do with my idea of the impossible situation. It would seem here that the analogue always arises in mediated communication (autobiographies, for instance).

Que un individuo quiera despertar en otro individuo recuerdos que no pertenecieron más que a un tercero, es una paradoja evidente. Ejecutar con despreocupación esa paradoja, es la inocente voluntad de toda biografía.

More thinking on the impossible situation

The revisions of this essay are almost complete. It contemplates baroque ecology through the novísimo interest in Early Modern poetry.

Take these lines from "Obsenidad de los paisajes":

esa falsa materia que el mar vislumbra en la prisión del cielo.

Ahora que somos dos (la tormenta lo dice) y la noche que cae nos

señala el camino con culebras de luz

The impossible situation is an interesting mixture of our normal experience in an environment and the dislocation of the human subject in that environment. While we might assume that the poet should convey his location in the scenery This dislocation is a symptom of the experimental work by various voices in the novísimo movement in the late-60s and 70s. These poets work through the analogue. Communication is no longer one-to-one, first person to second person. Instead, the Baroque leads them to breach into the 3rd person and finally no person (zero person). Important here is Maravall's concept of incompleteness. In prose or poetry, an author will inject mystery and magic into the form of the text. Readers are left with a kind of aura around storylines and environments. This also works to call attention to the fragementary nature of the text itself. Its backdrop is unstable. In painting, this becomes more clear as the observer is required to fill in the gaps and spaces left by the artist. For Maravall, Velázquez is a master of this technique. Splotches and blots of paint are used to create gaps in the visual piece. It is up to the human mind to fill in these spaces. And as Maravall states, this partial completion is often carried out with a modicum of liberty. It seems to me that this sort of esthetics leaves the concept of place in suspension, as an openness towards other life forms and objects.

I also argue that it is not the case that the lyrical voice is somehow destroyed or rejected, but rather it becomes re-worked through (another) renewed interest in the experimental work throughout the history of Castilian poetry (modernismo, vencecianismo, baroque poetry, decadentismo, etc).

Here the false material is the normal view of a landscape, a view not only produced by vision but also by affect. The impossible situation does not simply deny the possibility of horizons and emotions, but places them on unstable ground. As I put it at one point in the paper, the poem "dilutes the figure of meaning into the ground of the world".

Take these lines from "Obsenidad de los paisajes":

esa falsa materia que el mar vislumbra en la prisión del cielo.

Ahora que somos dos (la tormenta lo dice) y la noche que cae nos

señala el camino con culebras de luz

The impossible situation is an interesting mixture of our normal experience in an environment and the dislocation of the human subject in that environment. While we might assume that the poet should convey his location in the scenery This dislocation is a symptom of the experimental work by various voices in the novísimo movement in the late-60s and 70s. These poets work through the analogue. Communication is no longer one-to-one, first person to second person. Instead, the Baroque leads them to breach into the 3rd person and finally no person (zero person). Important here is Maravall's concept of incompleteness. In prose or poetry, an author will inject mystery and magic into the form of the text. Readers are left with a kind of aura around storylines and environments. This also works to call attention to the fragementary nature of the text itself. Its backdrop is unstable. In painting, this becomes more clear as the observer is required to fill in the gaps and spaces left by the artist. For Maravall, Velázquez is a master of this technique. Splotches and blots of paint are used to create gaps in the visual piece. It is up to the human mind to fill in these spaces. And as Maravall states, this partial completion is often carried out with a modicum of liberty. It seems to me that this sort of esthetics leaves the concept of place in suspension, as an openness towards other life forms and objects.

I also argue that it is not the case that the lyrical voice is somehow destroyed or rejected, but rather it becomes re-worked through (another) renewed interest in the experimental work throughout the history of Castilian poetry (modernismo, vencecianismo, baroque poetry, decadentismo, etc).

Here the false material is the normal view of a landscape, a view not only produced by vision but also by affect. The impossible situation does not simply deny the possibility of horizons and emotions, but places them on unstable ground. As I put it at one point in the paper, the poem "dilutes the figure of meaning into the ground of the world".

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Don Ramón's Aesthetic Meditations

Be like the nightingale,

which never looks at earth

from the green bough whereon it sings.

I read La lámpara maravillosa years ago and found its brand of mysticism alluring. Apparently the UM library only has the Robert Lima English translation. From what I can see it captures some of this allure from the original. His esthetic begins to fuse itself to natural imagery: "The subtlest intertwining of words is like the motion of caterpillars undulating beneath a ray of sunlight" (6). Yet the meditative voice of the author also works like an echo chamber. At the beginning of "The Ring of Gyges":

When I was a boy the glory of literature and the glory of adventure tempted me equally. It was a time full of dark voices, replete with a vast murmur, ardent and mystical, to which my being responded by becoming sonorous like a conch-shell (9).

Don Ramón begins from the "larval" stages of his formation, blurring voices with the written word his obscure "Aesthetic Discipline". To me, it is interesting that many of these Generation of 98 writers and thinkers use similar tropes to underscore their hopes for a regeneración of nation. Unamuno uses geological metaphors to discuss his concept of intrahistoria. For Unamuno, it is necessary to imagine the underground caverns and chambers of islands in order to understand the unveiled status of something like regeneración. Of course, Valle-Inclán limits his thinking to the esthetic. His nervous system is infused with these "dark voices". This murmuring remains negative and indeterminate, only experienced through the work of an echo.

Machado's "artificial" anti-rhetoric

«Orillas del Duero»

Se ha asomado una cigüeña a lo alto del campanario.

Girando en torno a la torre y al caserón solitario,

ya las golondrinas chillan. Pasaron del blanco invierno,

de nevascas y ventiscas los crudos soplos de infierno.

Es una tibia mañana.

El sol calienta un poquito la pobre tierra soriana.

Pasados los verdes pinos,

casi azules, primavera

se ve brotar en los finos

chopos de la carretera

y del río. El Duero corre, terso y mudo, mansamente.

El campo parece, más que joven, adolescente.

Entre las hierbas alguna humilde flor ha nacido,

azul o blanca. ¡Belleza del campo apenas florido,

y mística primaver!

¡Chopos del camino blanco, álamos de la ribera,

espuma de la montaña

ante la azul lejanía,

sol del día, claro día!

¡Hermosa tierra de España!

Gregorio Salvador's reading of Machado's "Orillas del Duero" (Soledades) is hilarious as well as provoking. In parts, his authoritative and technical reading throws down the gauntlet against Machado's stance as a voice emanating from the los pueblos y campos de Castilla. With a side jab, the imperative of the rhyme seems to dictate the presence of certain words -- like infierno, whose only apparent function is to chase down "invierno". It's the sort of rhyme that sticks out of the "naturalidad" of the language. Basically, it's a distraction. S's line of questioning is as follows: for a poet grounded in the prose of the world, why follow a word choice dictated by the formalities of a rhyme scheme?

Gregorio Salvador's reading of Machado's "Orillas del Duero" (Soledades) is hilarious as well as provoking. In parts, his authoritative and technical reading throws down the gauntlet against Machado's stance as a voice emanating from the los pueblos y campos de Castilla. With a side jab, the imperative of the rhyme seems to dictate the presence of certain words -- like infierno, whose only apparent function is to chase down "invierno". It's the sort of rhyme that sticks out of the "naturalidad" of the language. Basically, it's a distraction. S's line of questioning is as follows: for a poet grounded in the prose of the world, why follow a word choice dictated by the formalities of a rhyme scheme?

Then Salvador gets to deeper issues. The last line of the poem -- "¡Hermosa tierra de España!" -- creates a sensation of exuberance or radiance. Yet the language throughout the poem only diminishes such exuberance. "La descripción se quiebra." Salvador asserts that this diminished exuberance hollows out the "naturalidad" of the language: "es demasiado artificiosa para un poema tan sencillo".

It seems to me that this tension of artificiality is the strength of the poem. This occurs through a collision between the relayed scene and the poetic molding. Just as the subject matter follows a series of banks and boundaries at the site of the river, the final line "Hermosa tierra de España" is on the brink of collapsing into the river. The "exuberance" is cast out onto a rather dismal, dormant world, full of holes and distances. In this case, "the river" would be the space resurrected of the poem itself. If Machado should be labelled as anti-rhetorical, it should only be understood as a refusal to leave the poem contained in a prison of its own words. His ideas, sentiments and images are too personal. This to me seems to be the quieted exuberance at work here.

Se ha asomado una cigüeña a lo alto del campanario.

Girando en torno a la torre y al caserón solitario,

ya las golondrinas chillan. Pasaron del blanco invierno,

de nevascas y ventiscas los crudos soplos de infierno.

Es una tibia mañana.

El sol calienta un poquito la pobre tierra soriana.

Pasados los verdes pinos,

casi azules, primavera

se ve brotar en los finos

chopos de la carretera

y del río. El Duero corre, terso y mudo, mansamente.

El campo parece, más que joven, adolescente.

Entre las hierbas alguna humilde flor ha nacido,

azul o blanca. ¡Belleza del campo apenas florido,

y mística primaver!

¡Chopos del camino blanco, álamos de la ribera,

espuma de la montaña

ante la azul lejanía,

sol del día, claro día!

¡Hermosa tierra de España!

Gregorio Salvador's reading of Machado's "Orillas del Duero" (Soledades) is hilarious as well as provoking. In parts, his authoritative and technical reading throws down the gauntlet against Machado's stance as a voice emanating from the los pueblos y campos de Castilla. With a side jab, the imperative of the rhyme seems to dictate the presence of certain words -- like infierno, whose only apparent function is to chase down "invierno". It's the sort of rhyme that sticks out of the "naturalidad" of the language. Basically, it's a distraction. S's line of questioning is as follows: for a poet grounded in the prose of the world, why follow a word choice dictated by the formalities of a rhyme scheme?

Gregorio Salvador's reading of Machado's "Orillas del Duero" (Soledades) is hilarious as well as provoking. In parts, his authoritative and technical reading throws down the gauntlet against Machado's stance as a voice emanating from the los pueblos y campos de Castilla. With a side jab, the imperative of the rhyme seems to dictate the presence of certain words -- like infierno, whose only apparent function is to chase down "invierno". It's the sort of rhyme that sticks out of the "naturalidad" of the language. Basically, it's a distraction. S's line of questioning is as follows: for a poet grounded in the prose of the world, why follow a word choice dictated by the formalities of a rhyme scheme?Then Salvador gets to deeper issues. The last line of the poem -- "¡Hermosa tierra de España!" -- creates a sensation of exuberance or radiance. Yet the language throughout the poem only diminishes such exuberance. "La descripción se quiebra." Salvador asserts that this diminished exuberance hollows out the "naturalidad" of the language: "es demasiado artificiosa para un poema tan sencillo".

It seems to me that this tension of artificiality is the strength of the poem. This occurs through a collision between the relayed scene and the poetic molding. Just as the subject matter follows a series of banks and boundaries at the site of the river, the final line "Hermosa tierra de España" is on the brink of collapsing into the river. The "exuberance" is cast out onto a rather dismal, dormant world, full of holes and distances. In this case, "the river" would be the space resurrected of the poem itself. If Machado should be labelled as anti-rhetorical, it should only be understood as a refusal to leave the poem contained in a prison of its own words. His ideas, sentiments and images are too personal. This to me seems to be the quieted exuberance at work here.

Monday, September 12, 2011

Another thought on the tripartite theory

Last night I began to orient the different textually environments temporally (an authoritative preterite, a parodic present, and an undisclosed future involving lots of nonhumans). As I near the end of Graham Harman's The Quadruple Object, I am also beginning to think these spheres could be re-arranged spatially, kind of overlapping like venn diagrams.

Each sphere necessarily overlaps: the preformed interpretation of chivalric romances, the parodic recycling by Quijote as well as the product: the overwritting of the mountainous landscape with garbled visions of grandeur. This spatial arrangement might also allow some visual examinations of hierarchy and determinations. For example, what I previously called the "authoritative preterite" might be a circle encapsulating Quijote's present moment as well as the overwritten future (yes there is a sense of future perfect here). What is fascinating about Cervantes, of course, is his ability to poke holes in this hierarchical sphere of chivalry, pastoral ambience and even the picaresque (to only name a few). This suggests that these spheres are constantly decentered or displaced through an overflow of literary inventiveness.

Each sphere necessarily overlaps: the preformed interpretation of chivalric romances, the parodic recycling by Quijote as well as the product: the overwritting of the mountainous landscape with garbled visions of grandeur. This spatial arrangement might also allow some visual examinations of hierarchy and determinations. For example, what I previously called the "authoritative preterite" might be a circle encapsulating Quijote's present moment as well as the overwritten future (yes there is a sense of future perfect here). What is fascinating about Cervantes, of course, is his ability to poke holes in this hierarchical sphere of chivalry, pastoral ambience and even the picaresque (to only name a few). This suggests that these spheres are constantly decentered or displaced through an overflow of literary inventiveness.

Sunday, September 11, 2011

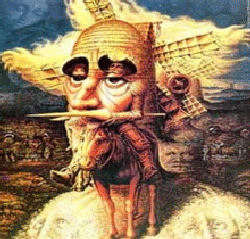

A tripartite theory of the environment in Quijote

I am always glad to simply re-affirm the brilliance of Cervantes in Don Quijote, especially concerning his parody of the major literary tendencies in his day. I have been re-reading a few chapters from Part one of DQ and loved the subtle shading between at least three different environments, all of which occur in the same location.

Chapter 25 is a great example of this inter-shading (or intersticing, for there are holes lurking). "La penitencia de don Quijote" produces at least three different interrelated environments. First, Quijote's penitence is predicated on his knowledge of Amadís (and his transference to Beltenebros). This first environment is the pre-determined encoded life of Quijote, based on the objects and whims in los libros de caballería. In this sense, the enshrined environment of Amadís is a preterite environment, encased in Q's apperception. For penitence to occur, the Quijote's form must mimic, that is, mock Amadís de Gaula. This takes us to the present moment of the text occurring within in the depths of the Sierra Morena mountain range. Here the proper names of knights and squires begin to melt into the decrepit, grotesque world of Quijote. Along with the proper name follows the values: "su prudencia, valor, valentía, sufrimiento, firmeza y amor". These values lose their transcendental meaning and take on a rather blurry imitatio, becoming embedded in a specific location. Finally, there is a future environment produced by this mimesis. Something Quijote himself evokes when he begins to speak to the objects that surround him:

¡Oh vosotros, quienquiera que seáis, rústicos, dioses que en este inhabitable lugar tenéis morada: oíd las quejas de este dedichado amante, a quien una luenga ausencia y unos imaginados celos han tráido a lamentarse entre asperezas y a quejarse de la dura condición.... ¡Oh solitarios árboles, que desde hoy en adelante habéis de hacer compañía a mi soledad, dad indicio con el blando movimiento de vuestras ramas que no os desagrade mi presencia! (238)

I find this tonal reworking of environment (and even re-ordering) to be similar to what Cervantes considered his failed pastoral work, La Galatea, a work proclaiming to operate between a real pastoral setting and the genre's idyllic imaginary.

Chapter 25 is a great example of this inter-shading (or intersticing, for there are holes lurking). "La penitencia de don Quijote" produces at least three different interrelated environments. First, Quijote's penitence is predicated on his knowledge of Amadís (and his transference to Beltenebros). This first environment is the pre-determined encoded life of Quijote, based on the objects and whims in los libros de caballería. In this sense, the enshrined environment of Amadís is a preterite environment, encased in Q's apperception. For penitence to occur, the Quijote's form must mimic, that is, mock Amadís de Gaula. This takes us to the present moment of the text occurring within in the depths of the Sierra Morena mountain range. Here the proper names of knights and squires begin to melt into the decrepit, grotesque world of Quijote. Along with the proper name follows the values: "su prudencia, valor, valentía, sufrimiento, firmeza y amor". These values lose their transcendental meaning and take on a rather blurry imitatio, becoming embedded in a specific location. Finally, there is a future environment produced by this mimesis. Something Quijote himself evokes when he begins to speak to the objects that surround him:

¡Oh vosotros, quienquiera que seáis, rústicos, dioses que en este inhabitable lugar tenéis morada: oíd las quejas de este dedichado amante, a quien una luenga ausencia y unos imaginados celos han tráido a lamentarse entre asperezas y a quejarse de la dura condición.... ¡Oh solitarios árboles, que desde hoy en adelante habéis de hacer compañía a mi soledad, dad indicio con el blando movimiento de vuestras ramas que no os desagrade mi presencia! (238)

I find this tonal reworking of environment (and even re-ordering) to be similar to what Cervantes considered his failed pastoral work, La Galatea, a work proclaiming to operate between a real pastoral setting and the genre's idyllic imaginary.

Monday, September 5, 2011

La humanización de los "objetos"

I am in the process of finalizing my reading lists for my preliminary exam. It's actually an enjoyable process to dig back through texts and commentaries that I have not seen for awhile. It's like returning to a place I have never been before. Glancing at the index to a commentary on Martín-Santos' Tiempo de silencio, I noticed an interesting subsection called "La humanización de los 'objetos'". Due to the borderline naturalism at work in Martín-Santos' text, humans beings are imprisoned in their social surroundings. The human as "object" is a given in Tiempo de silencio. Díaz Valcárcel is interested in how dehumanized figures seem to suddenly regain their human "plenitude". Characters suddenly pop out of their stereotypes and decrepitude state and act as if they were full of exuberance. Of course, this is a strength of Tiempo de silencio. It departs from the gutters and despair that dominate much of Spanish 1950s social realism.

For my part, I recently wrote on the nonhumans at work in Tiempo de destrucción, which often possess more "agency" than their human counterparts. Perhaps we should re-write this subsection and call it "La valorización de los objetos", leaving all ironies aside about humans as objects and wonder about the rats, science experiments and chabolas hard at work in this text.

For my part, I recently wrote on the nonhumans at work in Tiempo de destrucción, which often possess more "agency" than their human counterparts. Perhaps we should re-write this subsection and call it "La valorización de los objetos", leaving all ironies aside about humans as objects and wonder about the rats, science experiments and chabolas hard at work in this text.

Señas de identidad as Gumbi ambience

I recently expanded an essay comparing G's Makbara to Bolaño's Los detectives salvajes. The essay was for a conference on humor in Hispanic and Lusophone languages, which allowed me to think a lot about the style. And I think that Goytisolo's ambience is Gumbi-like. It stretches and diminishes what the reader would presume to be a stable location for a text.

Without delving too much into the work in that essay, I would also say that Goytisolo's first experimental novel, Señas de identidad, can also be described in these terms because it departs from the realism in his earlier work. Sdi expands and contracts with a Gumbi-like ambience.

Even if the text begins remarking on only pure coincidence between the fiction and actual events, this text is biographical. It sorts through the uncanny feeling of return to Spain after a sort of self-exile in France. If we stretched (in a Gumbi sort of way) out the real time at work in the novel, its frame would be three days. Yet its psychical time is gummed out for hundreds of pages. Of course, mainly label his sort of work and perception on Spain as stylistically self-serving (e.g. privileging aspects of historiography that are easily absorbed). However, the lapses and departures in Señas de identidad are not relying on the human psyche. Indeed, the narrator falls into gaps of past time (working in a sort of anticipatory way) through his re-encounter with objects. I would argue that these presences actually absorb the narrator and hence the narration into other times and locations.

Goytisolo's project, at this point, was a challenge to Spain's geographic and cultural signifiers. Flight and violence prohibit any stable notion of ambience here. Left unqualified, Goytisolo might be said to simply mobilize Gumbi ambience based on his own (nightmarish) experience with Castillian culture. However, human memory is not the only actor roaming around in the thick of this work.

Inopinadamente se encendió la luz. La noche había caído sin que tú lo advirtieras y, sentado todavía en el jardín, no podías distinguir el vuelo versátil de las golondrinas ni la orla rojiza del crepúsculo sobre el perfil sinuoso de las montañas. El álbum familiar permanecía entre tus manos, inútil yacen la sombra y, al incorporarte, te serviste otro vaso de Fefiñanes y lo apuraste de un sorbo. Las primeras estrellas pintaban encima del tejado y el gallo de la veleta recortaba apenas su silueta airose en el cielo oscuro. (76)

Is this simple description? The narrator, already addressing himself in the second person, gradually fades into the darkness alongside the photo album, the sparrows and the rusty brook. This darkness coincides with a like of active verbs in the first person. Instead, objects of memory guide readers through dark tunnels of time, spitting us out on new shores. It is kind of like the time bomb on the cover of his most recent novel (El exiliado de aquí y allá).

Without delving too much into the work in that essay, I would also say that Goytisolo's first experimental novel, Señas de identidad, can also be described in these terms because it departs from the realism in his earlier work. Sdi expands and contracts with a Gumbi-like ambience.

Even if the text begins remarking on only pure coincidence between the fiction and actual events, this text is biographical. It sorts through the uncanny feeling of return to Spain after a sort of self-exile in France. If we stretched (in a Gumbi sort of way) out the real time at work in the novel, its frame would be three days. Yet its psychical time is gummed out for hundreds of pages. Of course, mainly label his sort of work and perception on Spain as stylistically self-serving (e.g. privileging aspects of historiography that are easily absorbed). However, the lapses and departures in Señas de identidad are not relying on the human psyche. Indeed, the narrator falls into gaps of past time (working in a sort of anticipatory way) through his re-encounter with objects. I would argue that these presences actually absorb the narrator and hence the narration into other times and locations.

Goytisolo's project, at this point, was a challenge to Spain's geographic and cultural signifiers. Flight and violence prohibit any stable notion of ambience here. Left unqualified, Goytisolo might be said to simply mobilize Gumbi ambience based on his own (nightmarish) experience with Castillian culture. However, human memory is not the only actor roaming around in the thick of this work.

Inopinadamente se encendió la luz. La noche había caído sin que tú lo advirtieras y, sentado todavía en el jardín, no podías distinguir el vuelo versátil de las golondrinas ni la orla rojiza del crepúsculo sobre el perfil sinuoso de las montañas. El álbum familiar permanecía entre tus manos, inútil yacen la sombra y, al incorporarte, te serviste otro vaso de Fefiñanes y lo apuraste de un sorbo. Las primeras estrellas pintaban encima del tejado y el gallo de la veleta recortaba apenas su silueta airose en el cielo oscuro. (76)

Is this simple description? The narrator, already addressing himself in the second person, gradually fades into the darkness alongside the photo album, the sparrows and the rusty brook. This darkness coincides with a like of active verbs in the first person. Instead, objects of memory guide readers through dark tunnels of time, spitting us out on new shores. It is kind of like the time bomb on the cover of his most recent novel (El exiliado de aquí y allá).

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Advertencia as epigraph

I suppose most epigraphs should be considered warnings. This one is great:

Regalo al alma, tiros al sentido.

(Desengaño de amor en rimas)

Regalo al alma, tiros al sentido.

(Desengaño de amor en rimas)

Monday, August 8, 2011

In memoriam: Glissant asserting a baroque nature

A few years one of the biggest surprises in my MA coursework was a Caribbean literature class, a course taken out of necessity without much previous knowledge, which still provides leads and insights (e.g. exposure to the poetics of José Lezama Lima). A second unexpected gift was working through Édouard Glissant's Poétique de la Relation. Like many Carribean poets who take Deleuze and Guattari seriously into their account of archipelagic thinking, Glissant's work never seems as forced or militant (though he certainly engages multiple political fronts). I recently ran into his short piece, "Concerning a Baroque Abroad in the World".

What is important there is his attempt to pull the baroque crisis of subjectivity away from purely human qualifications. His essay is fundamentally about a Nature as a representation that works through proliferation rather than depth. The Baroque, understood as this crisis of meaning, also gives way to a rift between human history and Nature. (A consequence was the proliferation of landscape paintings in the 17th century.) Horror vaccui dictates extremes: anti-Nature, pro-Nature, counter-Nature, super-Nature. A positive outcome of this psychosis might be a moment of reformulation.

What Glissant means here is that the (historical) Baroque is an allergic reaction to the rationalist certainty of penetrating into the depths of things. Neobaroque thinking argues that these are historical patterns, repeating like archipelagos. Following William Egginton, among others, this seems to be good and bad -- depending on how the allergen and allergy is mobilized in a particular text.

Thus the Nature of the Baroque is about extreme inclusion. For Glissant the possibly more horrifying inverse is also true because inclusion also means here expansion and absorption into a Master worldview. To flip back again this absorption also folds in plurality into the monologic, fascist and centralized. It insures that the World understood qua World (or even Word) is unstable, expanding and boiling over. This points to the "moment of reformulation" mentioned above.

The Impossible situation: Obscenidad de los paisajes

Esta mañana somos dos los que observan el movimiento de las hojas, el cíclico murmullo de los primeros rostros que marchan al trabajo; dos los que miran lo impreciso de cuanto existe ajeno y nos rodea y a su manera nos define como ajenos también.

Fragmento de "Obscenidad de los paisajes"

Talens begins to unravel the obscenity of landscapes by calling attention to the alien, the distant (lo ajeno). The observation is at once simultaneous with the writing and, yet, the first person plural vanishes from the scene into the alien. This is the lyrical dislocation that Martín-Estudillo discusses in La mirada elíptica. It's not about banishing humans from the imaginary, but locating them within and without the alien: "y a su manera nos define como ajenos también."

Friday, July 29, 2011

Poetry in J. Goytisolo

Sometimes his more experimental prose is so defiantly violent it is hard to pinpoint. I have maintained that Makbara is entirely poetic in its distant engagement with orality.

It is also possible to add to the list these lines from the opening of Señas de identidad, which cycle through a few different mediums and thoughts in the same sentence:

lo que de lejos o de cerca huela a anti-español por haber rodado un breve documental de planificación defectuosa y chata pésimamente amalgamado y carente de garbo fotográfico y de poesía no es cosa que pueda extrañarnos acostumbrados como estamos a hechos y actitudes cuya triste reiteración revela el odio impotente de nuestros adversarios cualquiera...

Documentaries, photography and poetry work in connected cycles or spheres here. The comment about poetry certainly reminds me of what I tried to express to my students: we need poetry. Each briefly making contact before the sentence churns to another medium. In spite of the anger and bitterness in Goytisolo, the motor of his prose is always impressive. It tries to keep up. The last chapter in Makbara also comes to mind here, "Lectura del espacio en Xemaá-el-Fná", which also maintains insanely persistent prose-locomotives attempting to keep up with the encryption of space into place...

It is also possible to add to the list these lines from the opening of Señas de identidad, which cycle through a few different mediums and thoughts in the same sentence:

lo que de lejos o de cerca huela a anti-español por haber rodado un breve documental de planificación defectuosa y chata pésimamente amalgamado y carente de garbo fotográfico y de poesía no es cosa que pueda extrañarnos acostumbrados como estamos a hechos y actitudes cuya triste reiteración revela el odio impotente de nuestros adversarios cualquiera...

Documentaries, photography and poetry work in connected cycles or spheres here. The comment about poetry certainly reminds me of what I tried to express to my students: we need poetry. Each briefly making contact before the sentence churns to another medium. In spite of the anger and bitterness in Goytisolo, the motor of his prose is always impressive. It tries to keep up. The last chapter in Makbara also comes to mind here, "Lectura del espacio en Xemaá-el-Fná", which also maintains insanely persistent prose-locomotives attempting to keep up with the encryption of space into place...

Thursday, July 28, 2011

Senyora Carlota de Torres + the Dionysian instrument

As a trombone player, I know this sentence and its feeling (taken from a piece of criticism on Jesús Moncada's Camí de sirga). It is also, perchance, why trombone players are often found riding unicycles...

For example, the ageing Senyora Carlota de Torres, reminiscing about the celebrations held when the Second Republic was declared in 1931, is haunted by the memory of a trombone which stood out from the rest of the band.

Right. Trombone players and their axes clownishly make impressions...

For example, the ageing Senyora Carlota de Torres, reminiscing about the celebrations held when the Second Republic was declared in 1931, is haunted by the memory of a trombone which stood out from the rest of the band.

Right. Trombone players and their axes clownishly make impressions...

Wednesday, July 27, 2011

Ameztoy evading

Reading through this interview today with the Basque painter, Vicente Ameztoy. The last question was: "¿Cómo definiría su obra y su trabajo?". Really a hard question to even answer with a modicum of sincerity. To which he replies:

No lo sé porque yo la veo de una forma completamente distinta que cualquiera que ve el cuadro desde fuera. Además, supongo que dentro de unos años ya habrá especialistas que se encarguen de calificar mi obra.

I like two things about this response. The mention of an outside reality, in this case, that of the spectator, is very sincere and present in his painting. The outside (outside perception, outside the home, outside the polis) is mentioned repeatedly in the interview. It appears to work as a point of departure for the kinds of intertwining we see between landscapes and humans in his work. Like this:

Secondly, I always find the evading answer that a team of specialists will soon take over the responsibility of answering what it all means to be humorous -- because it is, on some level, very true.

No lo sé porque yo la veo de una forma completamente distinta que cualquiera que ve el cuadro desde fuera. Además, supongo que dentro de unos años ya habrá especialistas que se encarguen de calificar mi obra.

I like two things about this response. The mention of an outside reality, in this case, that of the spectator, is very sincere and present in his painting. The outside (outside perception, outside the home, outside the polis) is mentioned repeatedly in the interview. It appears to work as a point of departure for the kinds of intertwining we see between landscapes and humans in his work. Like this:

Secondly, I always find the evading answer that a team of specialists will soon take over the responsibility of answering what it all means to be humorous -- because it is, on some level, very true.

Nature in major and minor keys

Today I turned back to re-writing an essay on the baroque and J. Talens, thinking about his disordering and dismissal of landscapes and Nature. While certainly pertaining somewhat to the novísimos movement, Talens reacts differently to the conclusions after the end of la poesía social of the 1950s. There is the familiar refrain: “Si la poesía ya no puede hablar del mundo, hablará, al menos, de cómo otros poemas han hablado del mundo” (La coartada meta 56). This is a two-fold admission on the part of the poet: 1) complete sincerity on the part of lyric poetry appears to be problematic if not impossible 2) However, the lyrical I will continue to bob on the surface of an alyrical sea, through a variety of mouthpieces. This is the project of many novísimos, in particular Pere Gimferrer and Guillermo Carnero, who delve back into baroque poetry and their topos and voices (in particular ekphrastic poems about Venice). I have found this crisis of subjectivity and, therefore, of representation is also a crisis of backdrop, place, landscape and Nature. And the response is not negation, denial and *mere* postmodern irony, but of proliferation, continually churning out landscape even if it no longer appears possible to "order" them. Hence my interest in these lines from "No es el infierno, es la calle":

¿Qué ibas a hacer, ordenar los paisajes?…

Aquí sólo las cifras crecen y se multiplican.

The Baroque was about proliferation on major and minor scales (cf. Egginton's The Theater of Truth, pulling the terms, obviously, from D&G on Kafka). I follow Rem Koolhaas to think about space (and what we want to think of as place) in the same manner.

Sorting through Catalan with Perejaume

With no formal background in Catalan, I do find that an awareness of surrounding languages (French, Spanish and Portuguese) quite helpful for reading. And clearly the sense of Perejaume in El paisatge és rodó is one that I am sympathetic to: "La natura entesa com a objecte de l'explotació humana enfront de la natura bella per a ser contemplada és, en gran mesura, un fals dilema pel fet que la contemplació comporta, així mateix, una part d'explotació" (91). Perejaume goes on discuss the strong link created, maintained and forgotten on our (human part): the landscape is captured or apprehended in sight, given horizons and maintained as place, the stable signifier. As P. mentions about the capital of Garrotxa, Tal és l'Olot d'Olot.

The critique of landscape painting as estheticism clearly resonates with Sabadell Artiga's work in land art and installation pieces.

The critique of landscape painting as estheticism clearly resonates with Sabadell Artiga's work in land art and installation pieces.

Tuesday, July 19, 2011

Nature for poetics or poetics for Nature?

"The poetic real" -- J.V. Foix

Today I was confronted with same important question on a few different fronts. If a poet does not explicitly engage in an overt concern for the environment as an environmentalist or conservationist, how is it possible to argue that the work is indeed doing good for nonhuman entities?

The question is hugely important for my work right now. As I see it, following the work of others and in my own readings, the question is a most pertinent one for first wave ecocriticism, which insists on bringing Nature writing back into the forefront of academic research and pedagogy because it is overtly environmentalist, a term to be understood as historically specific, placed-based and nature-obsessed. As ecological criticism begins to expand outward into other cultural interactions with nonhumans the same esthetic dam does not always hold against the flood (Heise gives a great example of African American conceptions of the rural as an example of this).

My own view, following Morton and U. Heise in particular, maintains that texts can be more provocative if they are implicitly ecological. That is, they don't issue performative statements proclaiming some position, but rather enter into a certain type of relation with nonhumans. I usually find this non-position more subtle and productive because it becomes indicative of other positions yet to come. This might involve a conscious utilization of "Nature" for a poetics.

After being pressed on the question in some helpful comments, I found myself reading a commentary by Perejaume on Joan Brossa: "Let literature come down to earth". This paragraph and poem come from his marvelous essay:

That literature come down to earth, that both the direction of Brossa's images and the density and weight of the written work lead literature to touch down, presupposes, in effect, at the very least a certain literary conception, a certain earth(l)y conception. The earth on which Brossa writes, the earth of which Brossa speaks, the earth in which he inscribes himself, is as close and as remote as the closest and the most remote things we can imagine. The capacity of this earth is enormous, unfathomable, inexpressible. Brossa embraces, with an exceptional degree of breadth, the obsession with the marvelous and the common sense of reality. It is for this reason that literature and things are indissociable in his work. The enigma is totally earthly, manifest, as near and as vast as the earth itself, with no doctrines, with no dogma, to shield it. And Brossa wanted his literature to be as real as the earth.

And P. gives the following example from B.:

Harlequin I: He crosses a bridge.

Harlequin II: The ruin of a bridge.

H.I. A bridge over the river.

H. II: The bridge has no balustrades.

H. I: The bridge that will serve. The

H. II: bridges, exactly.

H. I: A bridge curves.

H. II: Over the bridge.

H. I: The bridge a woman sees.

And follows with a great phrase: "everything invokes the strangeness of what is closest, the experience of strangeness, the mysterious suspension that is produced in our understanding by the powerful presence of objects".

I do not want to suggest, however, that writers how openly identify themselves as part of some ecological/environmental movement are less worthy of discussion. This is certainly not the case (e.g. my interest in J. Riechmann). I think it is the case that we are not entirely certain about what this means yet and, as many have pointed out, environmentalism is an ideology historically specific to parts . To me, this is the exciting part about the work to be done.

Friday, July 8, 2011

José Ángel Valente

This will hopefully mark the beginning of a few different posts on some of my comments after reading and re-reading Los fragmentos de un libro futuro from José Ángel Valente, quite possibly one of the most difficult poets to fascinate me. (Right alongside, of course Lezama Lima -- indeed, they kept correspondence and read each other's work.)

After surveying the criticism on Valente, I recently confirmed some suspicions with a friend of mine: while there has been attention given to the poet, holes are lurking everywhere in the reading of Valente:

Saber de la palabra perdida, de la palabra que es la transparencia del ser. Antepalabra o palabra absoluta, todavía sin significación, o donde la significación es pura inminencia, matiz de todas las significaciones posibles: palabra naciente. Tal es al palabra del claro del bosque.

The careful attention to language (so surprising from a poet) perhaps speaks to the aforementioned lack of (some) critical attention. There is no overt gesture towards the social poetry of the 1950s, or any other ideological positioning for that matter. His literary touchstones may also be puzzling to one in search of overt radicality, for example Saint John of the Cross. Mysticism and christianity appear more overtly than other political shades.

In reference to the above, what is intriguing to me is the disucssion of language as something like a terrain, a comparison like Lacan's the unconscious is like a language (cf. David Abram). The claro del bosque (a clearing, also a title of M. Zambrano) is an iteration of the forest around it, but also a glimpse into an isolated moment. The reference to forests and trees is also surely a reference to Saussure. Elsewhere Valente writes of Saussure: "Un árbol se esconde en el bosque; una palabra, en las palabras. "Bajo las palabras del poema está sembrada, distribuida, o diseminada --disjecta membra--otra palabra, un nombre...". This leads us back to the question of the pure moment in the clearing of the linguistic forest, when is it that we recover or uncover la palabra naciente?

After surveying the criticism on Valente, I recently confirmed some suspicions with a friend of mine: while there has been attention given to the poet, holes are lurking everywhere in the reading of Valente:

Saber de la palabra perdida, de la palabra que es la transparencia del ser. Antepalabra o palabra absoluta, todavía sin significación, o donde la significación es pura inminencia, matiz de todas las significaciones posibles: palabra naciente. Tal es al palabra del claro del bosque.

The careful attention to language (so surprising from a poet) perhaps speaks to the aforementioned lack of (some) critical attention. There is no overt gesture towards the social poetry of the 1950s, or any other ideological positioning for that matter. His literary touchstones may also be puzzling to one in search of overt radicality, for example Saint John of the Cross. Mysticism and christianity appear more overtly than other political shades.

In reference to the above, what is intriguing to me is the disucssion of language as something like a terrain, a comparison like Lacan's the unconscious is like a language (cf. David Abram). The claro del bosque (a clearing, also a title of M. Zambrano) is an iteration of the forest around it, but also a glimpse into an isolated moment. The reference to forests and trees is also surely a reference to Saussure. Elsewhere Valente writes of Saussure: "Un árbol se esconde en el bosque; una palabra, en las palabras. "Bajo las palabras del poema está sembrada, distribuida, o diseminada --disjecta membra--otra palabra, un nombre...". This leads us back to the question of the pure moment in the clearing of the linguistic forest, when is it that we recover or uncover la palabra naciente?

Manifesto coding and decoding

A "manifesto against" is a strange type of manifesto because it delivers an affirmative position from the negation of another. Sabadell Artiga's "Manifest contra el paisatge" is a warranted negation because it reacts against paisajismo as a symptom of viewing Nature from an entirely human(ized) perspective. This "act" of viewing works like a freeze frame, stopping the confluence of relations between objects in a pure attempt to evaluate their esthetic "charm". Under the hypnosis of paisajismo, we are unable to act or comprehend the ecological crisis before us. I am fascinated by extracting the extremely nonhuman presence in this supposedly humanist act.