Due to the fact that my reading of Maravall is limited to his work on the Baroque (which I enjoy), I am surprised about the case he makes for Unamuno in his essay "De la intrahistoria a la historia". Of course, the essay takes place in a lengthy volume called Homenaje a Miguel de Unamuno. What surprises me is his upbeat tone. In La cultura del Barroco Maravall is famous for labeling the an entire nexus of culture as a form of state propaganda, a position that (some what) negates some contemporary positions.

In the field of peninsular literature (or what some of us prefer to call Iberian literary studies), the Generation of 98 is often viewed as an oversaturated object of inquiry. On this view, not only has each word of these authors been scrutinized in relation to ever other, but los noventayochistas tend to favor a vision of Spain as Castile (a blanket criticism that overlooks outliers -- like Valle-Inclán). Castile is the microcosm for Spain. All other regions are absorbed into the history and vision of an aged empire. Maravall says something different about Unamuno:

El «hombre sustancial» de que nos habla en «Visiones y comentarios», ese hombre que es alma y carne, que es espíritu y tierra-- esa tierra que es paisaje, creación humana recibida de sus antepasados-- nos lo presenta con frecuencia Unamuno como el individuo arraigado en la soledad campesina. Frente a él, «el hombre de la calle o el de la ciudad, el ciudadano, propiamente el elector, el de partido, es el político, de polis, ciudad; pero el otro, el interior, el de a sus solas, es el individuo del mundo--cosmos--, es el cósmico. (181)

Maravall's discussion begs a few important questions in today's attention or dismissal to Unamuno. They concern me because one aspect of my prelim is a sort of genealogy of literary landscapes in 20th century Spanish literature. I am working to re-invigorate thinking about Unamuno through his contact with a variety of Iberia's nationalisms and the multivalent concept of landscape. Unamuno was Basque. And his correspondence with Maragall is also fascinating. These connections push us to investigate the claim to some sort of cosmos in Unamuno. Indeed, as I have alluded to here, I think U's En torno al casticismo is saturated in dark dormant voices -- not only of humans but of nonhumans, geography and submerged caverns.

"La luz es el primer animal visible de lo invisible" --Lezama

Thursday, September 29, 2011

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Borges

Just after finishing the previous post, I am reviewing some information on JLB. I am teaching "El etnógrafo" y "Los dos reyes y los dos laberintos"and came across this idea, which has a lot to do with my idea of the impossible situation. It would seem here that the analogue always arises in mediated communication (autobiographies, for instance).

Que un individuo quiera despertar en otro individuo recuerdos que no pertenecieron más que a un tercero, es una paradoja evidente. Ejecutar con despreocupación esa paradoja, es la inocente voluntad de toda biografía.

More thinking on the impossible situation

The revisions of this essay are almost complete. It contemplates baroque ecology through the novísimo interest in Early Modern poetry.

Take these lines from "Obsenidad de los paisajes":

esa falsa materia que el mar vislumbra en la prisión del cielo.

Ahora que somos dos (la tormenta lo dice) y la noche que cae nos

señala el camino con culebras de luz

The impossible situation is an interesting mixture of our normal experience in an environment and the dislocation of the human subject in that environment. While we might assume that the poet should convey his location in the scenery This dislocation is a symptom of the experimental work by various voices in the novísimo movement in the late-60s and 70s. These poets work through the analogue. Communication is no longer one-to-one, first person to second person. Instead, the Baroque leads them to breach into the 3rd person and finally no person (zero person). Important here is Maravall's concept of incompleteness. In prose or poetry, an author will inject mystery and magic into the form of the text. Readers are left with a kind of aura around storylines and environments. This also works to call attention to the fragementary nature of the text itself. Its backdrop is unstable. In painting, this becomes more clear as the observer is required to fill in the gaps and spaces left by the artist. For Maravall, Velázquez is a master of this technique. Splotches and blots of paint are used to create gaps in the visual piece. It is up to the human mind to fill in these spaces. And as Maravall states, this partial completion is often carried out with a modicum of liberty. It seems to me that this sort of esthetics leaves the concept of place in suspension, as an openness towards other life forms and objects.

I also argue that it is not the case that the lyrical voice is somehow destroyed or rejected, but rather it becomes re-worked through (another) renewed interest in the experimental work throughout the history of Castilian poetry (modernismo, vencecianismo, baroque poetry, decadentismo, etc).

Here the false material is the normal view of a landscape, a view not only produced by vision but also by affect. The impossible situation does not simply deny the possibility of horizons and emotions, but places them on unstable ground. As I put it at one point in the paper, the poem "dilutes the figure of meaning into the ground of the world".

Take these lines from "Obsenidad de los paisajes":

esa falsa materia que el mar vislumbra en la prisión del cielo.

Ahora que somos dos (la tormenta lo dice) y la noche que cae nos

señala el camino con culebras de luz

The impossible situation is an interesting mixture of our normal experience in an environment and the dislocation of the human subject in that environment. While we might assume that the poet should convey his location in the scenery This dislocation is a symptom of the experimental work by various voices in the novísimo movement in the late-60s and 70s. These poets work through the analogue. Communication is no longer one-to-one, first person to second person. Instead, the Baroque leads them to breach into the 3rd person and finally no person (zero person). Important here is Maravall's concept of incompleteness. In prose or poetry, an author will inject mystery and magic into the form of the text. Readers are left with a kind of aura around storylines and environments. This also works to call attention to the fragementary nature of the text itself. Its backdrop is unstable. In painting, this becomes more clear as the observer is required to fill in the gaps and spaces left by the artist. For Maravall, Velázquez is a master of this technique. Splotches and blots of paint are used to create gaps in the visual piece. It is up to the human mind to fill in these spaces. And as Maravall states, this partial completion is often carried out with a modicum of liberty. It seems to me that this sort of esthetics leaves the concept of place in suspension, as an openness towards other life forms and objects.

I also argue that it is not the case that the lyrical voice is somehow destroyed or rejected, but rather it becomes re-worked through (another) renewed interest in the experimental work throughout the history of Castilian poetry (modernismo, vencecianismo, baroque poetry, decadentismo, etc).

Here the false material is the normal view of a landscape, a view not only produced by vision but also by affect. The impossible situation does not simply deny the possibility of horizons and emotions, but places them on unstable ground. As I put it at one point in the paper, the poem "dilutes the figure of meaning into the ground of the world".

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Don Ramón's Aesthetic Meditations

Be like the nightingale,

which never looks at earth

from the green bough whereon it sings.

I read La lámpara maravillosa years ago and found its brand of mysticism alluring. Apparently the UM library only has the Robert Lima English translation. From what I can see it captures some of this allure from the original. His esthetic begins to fuse itself to natural imagery: "The subtlest intertwining of words is like the motion of caterpillars undulating beneath a ray of sunlight" (6). Yet the meditative voice of the author also works like an echo chamber. At the beginning of "The Ring of Gyges":

When I was a boy the glory of literature and the glory of adventure tempted me equally. It was a time full of dark voices, replete with a vast murmur, ardent and mystical, to which my being responded by becoming sonorous like a conch-shell (9).

Don Ramón begins from the "larval" stages of his formation, blurring voices with the written word his obscure "Aesthetic Discipline". To me, it is interesting that many of these Generation of 98 writers and thinkers use similar tropes to underscore their hopes for a regeneración of nation. Unamuno uses geological metaphors to discuss his concept of intrahistoria. For Unamuno, it is necessary to imagine the underground caverns and chambers of islands in order to understand the unveiled status of something like regeneración. Of course, Valle-Inclán limits his thinking to the esthetic. His nervous system is infused with these "dark voices". This murmuring remains negative and indeterminate, only experienced through the work of an echo.

Machado's "artificial" anti-rhetoric

«Orillas del Duero»

Se ha asomado una cigüeña a lo alto del campanario.

Girando en torno a la torre y al caserón solitario,

ya las golondrinas chillan. Pasaron del blanco invierno,

de nevascas y ventiscas los crudos soplos de infierno.

Es una tibia mañana.

El sol calienta un poquito la pobre tierra soriana.

Pasados los verdes pinos,

casi azules, primavera

se ve brotar en los finos

chopos de la carretera

y del río. El Duero corre, terso y mudo, mansamente.

El campo parece, más que joven, adolescente.

Entre las hierbas alguna humilde flor ha nacido,

azul o blanca. ¡Belleza del campo apenas florido,

y mística primaver!

¡Chopos del camino blanco, álamos de la ribera,

espuma de la montaña

ante la azul lejanía,

sol del día, claro día!

¡Hermosa tierra de España!

Gregorio Salvador's reading of Machado's "Orillas del Duero" (Soledades) is hilarious as well as provoking. In parts, his authoritative and technical reading throws down the gauntlet against Machado's stance as a voice emanating from the los pueblos y campos de Castilla. With a side jab, the imperative of the rhyme seems to dictate the presence of certain words -- like infierno, whose only apparent function is to chase down "invierno". It's the sort of rhyme that sticks out of the "naturalidad" of the language. Basically, it's a distraction. S's line of questioning is as follows: for a poet grounded in the prose of the world, why follow a word choice dictated by the formalities of a rhyme scheme?

Gregorio Salvador's reading of Machado's "Orillas del Duero" (Soledades) is hilarious as well as provoking. In parts, his authoritative and technical reading throws down the gauntlet against Machado's stance as a voice emanating from the los pueblos y campos de Castilla. With a side jab, the imperative of the rhyme seems to dictate the presence of certain words -- like infierno, whose only apparent function is to chase down "invierno". It's the sort of rhyme that sticks out of the "naturalidad" of the language. Basically, it's a distraction. S's line of questioning is as follows: for a poet grounded in the prose of the world, why follow a word choice dictated by the formalities of a rhyme scheme?

Then Salvador gets to deeper issues. The last line of the poem -- "¡Hermosa tierra de España!" -- creates a sensation of exuberance or radiance. Yet the language throughout the poem only diminishes such exuberance. "La descripción se quiebra." Salvador asserts that this diminished exuberance hollows out the "naturalidad" of the language: "es demasiado artificiosa para un poema tan sencillo".

It seems to me that this tension of artificiality is the strength of the poem. This occurs through a collision between the relayed scene and the poetic molding. Just as the subject matter follows a series of banks and boundaries at the site of the river, the final line "Hermosa tierra de España" is on the brink of collapsing into the river. The "exuberance" is cast out onto a rather dismal, dormant world, full of holes and distances. In this case, "the river" would be the space resurrected of the poem itself. If Machado should be labelled as anti-rhetorical, it should only be understood as a refusal to leave the poem contained in a prison of its own words. His ideas, sentiments and images are too personal. This to me seems to be the quieted exuberance at work here.

Se ha asomado una cigüeña a lo alto del campanario.

Girando en torno a la torre y al caserón solitario,

ya las golondrinas chillan. Pasaron del blanco invierno,

de nevascas y ventiscas los crudos soplos de infierno.

Es una tibia mañana.

El sol calienta un poquito la pobre tierra soriana.

Pasados los verdes pinos,

casi azules, primavera

se ve brotar en los finos

chopos de la carretera

y del río. El Duero corre, terso y mudo, mansamente.

El campo parece, más que joven, adolescente.

Entre las hierbas alguna humilde flor ha nacido,

azul o blanca. ¡Belleza del campo apenas florido,

y mística primaver!

¡Chopos del camino blanco, álamos de la ribera,

espuma de la montaña

ante la azul lejanía,

sol del día, claro día!

¡Hermosa tierra de España!

Gregorio Salvador's reading of Machado's "Orillas del Duero" (Soledades) is hilarious as well as provoking. In parts, his authoritative and technical reading throws down the gauntlet against Machado's stance as a voice emanating from the los pueblos y campos de Castilla. With a side jab, the imperative of the rhyme seems to dictate the presence of certain words -- like infierno, whose only apparent function is to chase down "invierno". It's the sort of rhyme that sticks out of the "naturalidad" of the language. Basically, it's a distraction. S's line of questioning is as follows: for a poet grounded in the prose of the world, why follow a word choice dictated by the formalities of a rhyme scheme?

Gregorio Salvador's reading of Machado's "Orillas del Duero" (Soledades) is hilarious as well as provoking. In parts, his authoritative and technical reading throws down the gauntlet against Machado's stance as a voice emanating from the los pueblos y campos de Castilla. With a side jab, the imperative of the rhyme seems to dictate the presence of certain words -- like infierno, whose only apparent function is to chase down "invierno". It's the sort of rhyme that sticks out of the "naturalidad" of the language. Basically, it's a distraction. S's line of questioning is as follows: for a poet grounded in the prose of the world, why follow a word choice dictated by the formalities of a rhyme scheme?Then Salvador gets to deeper issues. The last line of the poem -- "¡Hermosa tierra de España!" -- creates a sensation of exuberance or radiance. Yet the language throughout the poem only diminishes such exuberance. "La descripción se quiebra." Salvador asserts that this diminished exuberance hollows out the "naturalidad" of the language: "es demasiado artificiosa para un poema tan sencillo".

It seems to me that this tension of artificiality is the strength of the poem. This occurs through a collision between the relayed scene and the poetic molding. Just as the subject matter follows a series of banks and boundaries at the site of the river, the final line "Hermosa tierra de España" is on the brink of collapsing into the river. The "exuberance" is cast out onto a rather dismal, dormant world, full of holes and distances. In this case, "the river" would be the space resurrected of the poem itself. If Machado should be labelled as anti-rhetorical, it should only be understood as a refusal to leave the poem contained in a prison of its own words. His ideas, sentiments and images are too personal. This to me seems to be the quieted exuberance at work here.

Monday, September 12, 2011

Another thought on the tripartite theory

Last night I began to orient the different textually environments temporally (an authoritative preterite, a parodic present, and an undisclosed future involving lots of nonhumans). As I near the end of Graham Harman's The Quadruple Object, I am also beginning to think these spheres could be re-arranged spatially, kind of overlapping like venn diagrams.

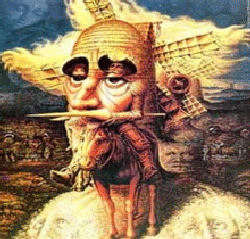

Each sphere necessarily overlaps: the preformed interpretation of chivalric romances, the parodic recycling by Quijote as well as the product: the overwritting of the mountainous landscape with garbled visions of grandeur. This spatial arrangement might also allow some visual examinations of hierarchy and determinations. For example, what I previously called the "authoritative preterite" might be a circle encapsulating Quijote's present moment as well as the overwritten future (yes there is a sense of future perfect here). What is fascinating about Cervantes, of course, is his ability to poke holes in this hierarchical sphere of chivalry, pastoral ambience and even the picaresque (to only name a few). This suggests that these spheres are constantly decentered or displaced through an overflow of literary inventiveness.

Each sphere necessarily overlaps: the preformed interpretation of chivalric romances, the parodic recycling by Quijote as well as the product: the overwritting of the mountainous landscape with garbled visions of grandeur. This spatial arrangement might also allow some visual examinations of hierarchy and determinations. For example, what I previously called the "authoritative preterite" might be a circle encapsulating Quijote's present moment as well as the overwritten future (yes there is a sense of future perfect here). What is fascinating about Cervantes, of course, is his ability to poke holes in this hierarchical sphere of chivalry, pastoral ambience and even the picaresque (to only name a few). This suggests that these spheres are constantly decentered or displaced through an overflow of literary inventiveness.

Sunday, September 11, 2011

A tripartite theory of the environment in Quijote

I am always glad to simply re-affirm the brilliance of Cervantes in Don Quijote, especially concerning his parody of the major literary tendencies in his day. I have been re-reading a few chapters from Part one of DQ and loved the subtle shading between at least three different environments, all of which occur in the same location.

Chapter 25 is a great example of this inter-shading (or intersticing, for there are holes lurking). "La penitencia de don Quijote" produces at least three different interrelated environments. First, Quijote's penitence is predicated on his knowledge of Amadís (and his transference to Beltenebros). This first environment is the pre-determined encoded life of Quijote, based on the objects and whims in los libros de caballería. In this sense, the enshrined environment of Amadís is a preterite environment, encased in Q's apperception. For penitence to occur, the Quijote's form must mimic, that is, mock Amadís de Gaula. This takes us to the present moment of the text occurring within in the depths of the Sierra Morena mountain range. Here the proper names of knights and squires begin to melt into the decrepit, grotesque world of Quijote. Along with the proper name follows the values: "su prudencia, valor, valentía, sufrimiento, firmeza y amor". These values lose their transcendental meaning and take on a rather blurry imitatio, becoming embedded in a specific location. Finally, there is a future environment produced by this mimesis. Something Quijote himself evokes when he begins to speak to the objects that surround him:

¡Oh vosotros, quienquiera que seáis, rústicos, dioses que en este inhabitable lugar tenéis morada: oíd las quejas de este dedichado amante, a quien una luenga ausencia y unos imaginados celos han tráido a lamentarse entre asperezas y a quejarse de la dura condición.... ¡Oh solitarios árboles, que desde hoy en adelante habéis de hacer compañía a mi soledad, dad indicio con el blando movimiento de vuestras ramas que no os desagrade mi presencia! (238)

I find this tonal reworking of environment (and even re-ordering) to be similar to what Cervantes considered his failed pastoral work, La Galatea, a work proclaiming to operate between a real pastoral setting and the genre's idyllic imaginary.

Chapter 25 is a great example of this inter-shading (or intersticing, for there are holes lurking). "La penitencia de don Quijote" produces at least three different interrelated environments. First, Quijote's penitence is predicated on his knowledge of Amadís (and his transference to Beltenebros). This first environment is the pre-determined encoded life of Quijote, based on the objects and whims in los libros de caballería. In this sense, the enshrined environment of Amadís is a preterite environment, encased in Q's apperception. For penitence to occur, the Quijote's form must mimic, that is, mock Amadís de Gaula. This takes us to the present moment of the text occurring within in the depths of the Sierra Morena mountain range. Here the proper names of knights and squires begin to melt into the decrepit, grotesque world of Quijote. Along with the proper name follows the values: "su prudencia, valor, valentía, sufrimiento, firmeza y amor". These values lose their transcendental meaning and take on a rather blurry imitatio, becoming embedded in a specific location. Finally, there is a future environment produced by this mimesis. Something Quijote himself evokes when he begins to speak to the objects that surround him:

¡Oh vosotros, quienquiera que seáis, rústicos, dioses que en este inhabitable lugar tenéis morada: oíd las quejas de este dedichado amante, a quien una luenga ausencia y unos imaginados celos han tráido a lamentarse entre asperezas y a quejarse de la dura condición.... ¡Oh solitarios árboles, que desde hoy en adelante habéis de hacer compañía a mi soledad, dad indicio con el blando movimiento de vuestras ramas que no os desagrade mi presencia! (238)

I find this tonal reworking of environment (and even re-ordering) to be similar to what Cervantes considered his failed pastoral work, La Galatea, a work proclaiming to operate between a real pastoral setting and the genre's idyllic imaginary.

Monday, September 5, 2011

La humanización de los "objetos"

I am in the process of finalizing my reading lists for my preliminary exam. It's actually an enjoyable process to dig back through texts and commentaries that I have not seen for awhile. It's like returning to a place I have never been before. Glancing at the index to a commentary on Martín-Santos' Tiempo de silencio, I noticed an interesting subsection called "La humanización de los 'objetos'". Due to the borderline naturalism at work in Martín-Santos' text, humans beings are imprisoned in their social surroundings. The human as "object" is a given in Tiempo de silencio. Díaz Valcárcel is interested in how dehumanized figures seem to suddenly regain their human "plenitude". Characters suddenly pop out of their stereotypes and decrepitude state and act as if they were full of exuberance. Of course, this is a strength of Tiempo de silencio. It departs from the gutters and despair that dominate much of Spanish 1950s social realism.

For my part, I recently wrote on the nonhumans at work in Tiempo de destrucción, which often possess more "agency" than their human counterparts. Perhaps we should re-write this subsection and call it "La valorización de los objetos", leaving all ironies aside about humans as objects and wonder about the rats, science experiments and chabolas hard at work in this text.

For my part, I recently wrote on the nonhumans at work in Tiempo de destrucción, which often possess more "agency" than their human counterparts. Perhaps we should re-write this subsection and call it "La valorización de los objetos", leaving all ironies aside about humans as objects and wonder about the rats, science experiments and chabolas hard at work in this text.

Señas de identidad as Gumbi ambience

I recently expanded an essay comparing G's Makbara to Bolaño's Los detectives salvajes. The essay was for a conference on humor in Hispanic and Lusophone languages, which allowed me to think a lot about the style. And I think that Goytisolo's ambience is Gumbi-like. It stretches and diminishes what the reader would presume to be a stable location for a text.

Without delving too much into the work in that essay, I would also say that Goytisolo's first experimental novel, Señas de identidad, can also be described in these terms because it departs from the realism in his earlier work. Sdi expands and contracts with a Gumbi-like ambience.

Even if the text begins remarking on only pure coincidence between the fiction and actual events, this text is biographical. It sorts through the uncanny feeling of return to Spain after a sort of self-exile in France. If we stretched (in a Gumbi sort of way) out the real time at work in the novel, its frame would be three days. Yet its psychical time is gummed out for hundreds of pages. Of course, mainly label his sort of work and perception on Spain as stylistically self-serving (e.g. privileging aspects of historiography that are easily absorbed). However, the lapses and departures in Señas de identidad are not relying on the human psyche. Indeed, the narrator falls into gaps of past time (working in a sort of anticipatory way) through his re-encounter with objects. I would argue that these presences actually absorb the narrator and hence the narration into other times and locations.

Goytisolo's project, at this point, was a challenge to Spain's geographic and cultural signifiers. Flight and violence prohibit any stable notion of ambience here. Left unqualified, Goytisolo might be said to simply mobilize Gumbi ambience based on his own (nightmarish) experience with Castillian culture. However, human memory is not the only actor roaming around in the thick of this work.

Inopinadamente se encendió la luz. La noche había caído sin que tú lo advirtieras y, sentado todavía en el jardín, no podías distinguir el vuelo versátil de las golondrinas ni la orla rojiza del crepúsculo sobre el perfil sinuoso de las montañas. El álbum familiar permanecía entre tus manos, inútil yacen la sombra y, al incorporarte, te serviste otro vaso de Fefiñanes y lo apuraste de un sorbo. Las primeras estrellas pintaban encima del tejado y el gallo de la veleta recortaba apenas su silueta airose en el cielo oscuro. (76)

Is this simple description? The narrator, already addressing himself in the second person, gradually fades into the darkness alongside the photo album, the sparrows and the rusty brook. This darkness coincides with a like of active verbs in the first person. Instead, objects of memory guide readers through dark tunnels of time, spitting us out on new shores. It is kind of like the time bomb on the cover of his most recent novel (El exiliado de aquí y allá).

Without delving too much into the work in that essay, I would also say that Goytisolo's first experimental novel, Señas de identidad, can also be described in these terms because it departs from the realism in his earlier work. Sdi expands and contracts with a Gumbi-like ambience.

Even if the text begins remarking on only pure coincidence between the fiction and actual events, this text is biographical. It sorts through the uncanny feeling of return to Spain after a sort of self-exile in France. If we stretched (in a Gumbi sort of way) out the real time at work in the novel, its frame would be three days. Yet its psychical time is gummed out for hundreds of pages. Of course, mainly label his sort of work and perception on Spain as stylistically self-serving (e.g. privileging aspects of historiography that are easily absorbed). However, the lapses and departures in Señas de identidad are not relying on the human psyche. Indeed, the narrator falls into gaps of past time (working in a sort of anticipatory way) through his re-encounter with objects. I would argue that these presences actually absorb the narrator and hence the narration into other times and locations.

Goytisolo's project, at this point, was a challenge to Spain's geographic and cultural signifiers. Flight and violence prohibit any stable notion of ambience here. Left unqualified, Goytisolo might be said to simply mobilize Gumbi ambience based on his own (nightmarish) experience with Castillian culture. However, human memory is not the only actor roaming around in the thick of this work.

Inopinadamente se encendió la luz. La noche había caído sin que tú lo advirtieras y, sentado todavía en el jardín, no podías distinguir el vuelo versátil de las golondrinas ni la orla rojiza del crepúsculo sobre el perfil sinuoso de las montañas. El álbum familiar permanecía entre tus manos, inútil yacen la sombra y, al incorporarte, te serviste otro vaso de Fefiñanes y lo apuraste de un sorbo. Las primeras estrellas pintaban encima del tejado y el gallo de la veleta recortaba apenas su silueta airose en el cielo oscuro. (76)

Is this simple description? The narrator, already addressing himself in the second person, gradually fades into the darkness alongside the photo album, the sparrows and the rusty brook. This darkness coincides with a like of active verbs in the first person. Instead, objects of memory guide readers through dark tunnels of time, spitting us out on new shores. It is kind of like the time bomb on the cover of his most recent novel (El exiliado de aquí y allá).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)